2024 marks the 50th Pride Parade in San Diego. Here’s a look back at the last 49 years of Pride festivities with 1974 as a special treat!

In 1974, two gay rights marches occurred that frequently get conflated. The language of “Pride” was not yet used although Stonewall and Christopher Street commemorations and die-ins were organized by San Diegans between 1970 and 1974. On the fifth anniversary of Stonewall, the Gay Center for Social Services (today’s LGBT Center) held a fundraiser with a potluck and yard sale. Some say this was followed by an impromptu march. The second large protest occurred in September after the San Diego Police Department secretly observed the bathrooms of the May Company and arrested eight men for “felony sex perversion.” Their names, occupations and addresses were published in the San Diego Union, sparking a protest by local activists, as pictured above. Eventually the charges were dropped. This march is a reminder LGBTQ+ advocacy in San Diego did not start with Pride and is never limited to Pride. Plus, this photo makes the collection an even 50 photos since the fiftieth Pride Parade takes place on July 20, 2024.

The first official “Gay Pride Day” received a permit and was held in 1975 on the anniversary of the Stonewall riots. Here a solo woman and stroller observed the decorated cars and 400 people carrying protest signs. For today’s Pride Parade, there are over 200,000 spectators.

Of the day, Nicole Murray Ramirez said, “It was a scary and lonely march down Broadway … Nobody applauded. And most gay people didn’t come out to the sidelines because they were afraid.”

This photo was taken by Gary Gulley, who was involved in the San Diego chapter of the Gay Liberation Front until it folded. Then he founded the SDSU Gay Students Union, which still exists today as the LGBT Students Union. A printer by trade, Gulley helped print flyers and circulate information to the community in the 1970s.

On the 200th anniversary of the United States of America in 1976, Pride marchers bore a large purple sign reading “200 Years of Freedom for Whom?” Even in the second year of Pride in San Diego, conflicts began over who gets to define the Pride movement and who it includes. According to an essay by Gabriella Garcia about a flyer from the time, the Pride committee in 1976 barred “political” signs and then any signs for specific organizations or groups. This was a reaction to pressure from the Imperial Court of San Diego and the San Diego Tavern Guild over the prevalence of Social Workers’ Party in the first Pride march. Many organizations, including the Center, Metropolitan Community Church (MCC), and Dignity Center, declined to participate after the decision to focus only on a monolithic, flattened “Gay Spirit.” Photos of the parade document signs reading “Lesbians Against Senate Bill 1,” showing not all individuals followed rules meant to depoliticize Pride.

In 1977, marchers took up a lane of traffic on Fifth Avenue. One protester bore a sign reading “We Are Your Children,” likely in reference to homophobic fears that LGBTQ+ people threatened children’s wellbeing. In this year, Anita Bryant responded to the growing gay rights movement with a counter movement to “protect children” by firing gay and lesbian teachers in Florida. Following her example in California, State Senator Stephen Briggs introduced an initiative to fire all openly gay teachers in public schools and teachers in support of gay rights. After massive efforts from local activists, California voters rejected the ballot measure in Nov., 1978.

This sign from 1978 includes a pink triangle with a power fist inside. The pink triangle was originated by the Nazis to mark homosexual prisoners and was later reclaimed by the gay rights movement. Act Up, the HIV/AIDS organization, used the pink triangle a decade later. However, artists with the protest group inverted the triangle so it pointed up. The inverted triangle was meant to represent an active fight against institutions ignoring the suffering of people with AIDS, rather than a passive acceptance of death.

The person holding the American flag blocking part of the sign is not identified. With their face turned away, it is unclear who they are, although this editor speculates they could be an early intersex or trans activist. While it was referred to as the gay and lesbian rights movement at the time, activists from diverse genders and sexualities have always been a part of the movement.

Thomas Carey smiled while holding a sign reading “Gay People Come in All Colors.” Carey was a member of the committee that founded The Center in 1973, helped fundraise to found The Center, and hosted Gay Self-Development meetings. His sign counters the false narrative that the gay rights movement was a niche movement of middle class white people.

A fanciful float in the 1980 Pride Parade reads “unidos triunfaremos,” which means “united we will triumph.” A queen waved at the crowd from atop it.

The beginning of this decade started in division, with the women‘s caucus refusing to participate in Pride. By the end though, the AIDS crisis caused the LGBTQ+ movement to unite as never before. The community also diversified with new groups forming such as Gay and Lesbian Latino Organization, Lesbians and Gays of African Descent United, Nations of the Four Directions (founded by Native Americans), Gay/Lesbian Asian-Pacific Islanders Social Support and Neutral Corner for transgender people.

This photo ran in UpDate Newspaper, a Southern California gay publication which ran from 1980 to 2006.

Behind a “Rudy de la Mor” car, the San Diego Gay Bird marched in a parade, year unknown. This costumed individual appeared in multiple photographs throughout the ‘80s and early ‘90s, including posing beside one of the most significant LGBTQ+ rights pioneers in San Diego: Jess Jessop. According to a conversation on the Lambda Archives Flickr page, the Gay Bird was meant to be the queer counterpart of the San Diego Chicken. For those unaware, the San Diego Chicken is the most influential mascot in history, reviving interest in the Padres and leading to all MLB teams and even other sports teams to adopt mascots of their own.

This 1982 photo shows the growing Pride Festival. Doug Moore took this photo, later donating it to Jess Jessop in 1987 when Jessop founded Lambda Archives. Moore has gone on to be a key figure in preserving LGBTQ+ history in San Diego. “We were all young and full of energy. I’m just happy to have been a part of it and to be able to see where our efforts have taken us,” Moore wrote recently.

1982 was also the year Moore built a list of contacts from each of the Pride organizations in the United States. This contact list enabled Pride organizations to come together for a conference and continue collaborating until forming the coalition InterPride, which is now a global organization that celebrated its 40th year at a conference in San Diego last fall.

Nicole Murray Ramirez addressed a crowd at the rally following the Pride Parade in 1983. Ramirez was one of the people to first take the microphone at the rally at Balboa Park after the first Gay Pride Day in 1975. In honor of this, he became the parade’s Grand Marshal on its 30th anniversary. He is still active today as a Latino civil rights activist and leader in the Imperial Court of the Americas.

A woman marching in the 1984 Pride Parade bears a sign reading “It’s All About Love.” In the height of the AIDS crisis, Bible Missionary Fellowship, a conservative church in Santee, wore hazmat suits on University Ave. on Hillcrest with signs declaring the unfolding tragedy was God’s punishment for homosexuality, according to lesbian historian Dr. Lillian Faderman. A photo from Chris Kehoe in this period documents a sign saying “Don’t Feed the Fundies” at a Pride festival, urging people to keep celebrating without engaging counter protesters.

An aerial view of the festival in 1985, which continued to grow as an explosive number of LGBTQ+ and AIDS assistance organizations were formed in the ’80s. Lesbians formed the Blood Sisters to donate blood to AIDS patients while gay men were barred from donating blood; the Imperial Court raised money for an AIDS Assistance Fund; and Mama’s Kitchen and Special Delivery brought meals to patients. The AIDS Walk/Walk for Life was founded as another way to raise money and awareness about the epidemic. Auntie Helen’s Fluff ‘n Fold provided laundry services to home bound patients, writes Faderman. Later, the Truax House in Bankers Hill, named after Brad Truax, physician and early AIDS activist who died from the disease in 1988, opened to provide hospice care for AIDS patients.

This photo was taken by future Assembly member Chris Kehoe, the first LGBT+-elected in San Diego. It shows police piling on 39-year-old Brian Barlow, a gay man from San Francisco who was in the San Francisco Gay Freedom Marching Band. The officers carried Barlow away after tackling him here. She wrote that SDPD was egged on by anti-LGBT+ protesters visible behind the police.

At the Pride Festival in 1987, 289 crosses were laid out for local victims of AIDS. A sign reads “We have waited too long… We have lost too many.” In October of that year, local civil rights activists went to Washington D.C. for the Second March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, demanding the Reagan administration acknowledge the AIDS crisis.

In the 1988 parade, shirtless men with black armbands ride in “The Hug Mobile.” Pride was about to go in a more professional direction the following year, with Tim Williams hired as Executive Director by Chris Kehoe, Neil Good and others. Williams would not be able to stay long in the position due to losing his battle with AIDS, leaving his women aides in charge.

Deidre McCalla played a guitar in front of a large design that says “15/20 San Diego/Stonewall A Generation of Pride.” It marked the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots and 15th anniversary of the first Gay Pride Day in San Diego. McCalla is a self-described Black woman, mother, lesbian, feminist who grew up in New York’s folk scene before becoming a singer-songwriter based in Northern California.

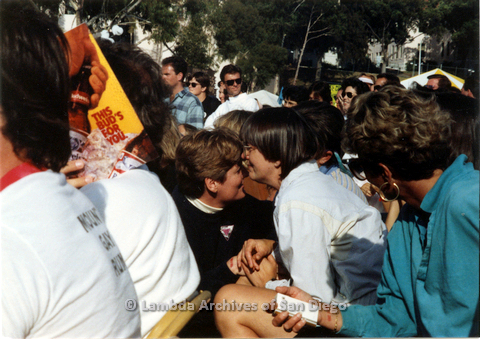

In this photo by Edna Myers, two women nuzzle each other and hold hands during the 1990 Pride Festival.

The Pride Parade that year included the first openly-gay police officer marching, John Graham. He marched alone with a blacked-out SUV of closeted police officers following him. As he marched, law enforcement personnel guarding parade goers turned their backs on him. Pride Executive Director Barbra Blake received death threats over Graham’s participation.

Drag queens waved from a car in the parade. 1991 marked the permanent move of the event from June to July to avoid San Diego’s “June Gloom” weather pattern. For touring entertainers, it also meant they could perform at Pride events throughout the nation with less date conflicts.

This year ended on a tragic note as in December, three men brutally attacked a group of friends walking down University Ave. while yelling “faggots,” making it a hate crime. Seventeen-year-old John Robert Wear was stabbed to death in the incident.

SDPD Police Chief Bob Burgreen marched in uniform at the front of the SDPD contingent in the 1992 parade. The first out officer, Graham, (left) marched with other out officers. By the end of the year, the Sheriff’s Department and San Diego Unified School District added policies banning discrimination against lesbian and gay students, people and employees. The Sheriff’s Department would not march in the Pride Parade until 1996.

This photo of leather men with fundamentalist Christian protesters behind them was taken by Chris Kehoe. She was elected to City Council District 3 in 1993, becoming the first LGBTQ+ elected in San Diego. Previously, she chaired the county committee to oppose Prop 64 in 1986 which would have quarantined HIV patients. Plus, she worked on the campaign of openly gay candidate Neil Good in 1987, who was not elected. Since her election, the District 3 seat has always been occupied by a lesbian or gay person.

A performer named Bianca lounged atop a car advertising the Brass Rail with a sign saying “Ladies by Choice” in 1994. The Rail is the oldest gay bar in San Diego after remaining open since the 1930s. It operates today at 3796 Fifth Ave.

Pride incorporated as a nonprofit in 1994. The parade route and festival grounds familiar to people today originated from this year as well.

Ophelia Left greeted the crowd. She represented the Imperial Court in 1995. The San Diego chapter was founded in 1973, eight years after José Sarria founded the Imperial Court System in San Francisco, and the same year Dignity, Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) and the Center were getting organized. The Imperial Court is one of the longstanding local LGBTQ+ organizations.

Mr. Eagle 1996, Scotty Moats, waved at the crowd, including those seated on rooftops along University Ave., in a leather chariot. San Diego had an active leather community for many years at this point, with annual event LeatherFest raising money for AIDS organizations like Special Delivery and Auntie Helen’s. Gay Leathermen Only was founded in 1996.

1997 was a major milestone in community interest in the Pride Parade. For the first time, 100,000 spectators swarmed Hillcrest to view contingents like the Gay Vietnamese Alliance and the Asian Pacific Islander Community AIDS Project.

In 1998, San Diego City Council finally repealed a 1966 ordinance that prohibited the appearance “in a public place, or in a place open to public view, in apparel customarily worn by the opposite sex.” According to Faderman, the ordinance that criminalized transgender people’s gender expression was initially passed with claims sailors headed to the Vietnam war could be seduced by men posing as women, taken to a hotel room, and robbed. At the time, there was little distinction between gender and sexuality, so it was assumed “deceitful” transgender people were all engaging in illegal homosexual acts.

This photo shows a tender moment as a man holds his smiling partner. The 1999 parade was marred by a tear gas attack from an unknown assailant. A tear gas canister was thrown into a group of 70 people — some children and babies in strollers — making up the Family Matters contingent. Three people were hospitalized. After the gas dispersed and affected people received care, the parade continued to the finish.

Kink and nudity at Pride have been a perennial debate – often centered around whether celebrating diverse sexualities is still the point of Pride or if it’s evolved into a family-friendly, sanitized day. The debate is also about tactics: does assimilation and respectability politics work or progressive movements that challenge people’s beliefs about what is normal? These debates are often proxy fights about whether Pride is still a political event (it is).

Starting in 1994, Dyke March focused on lesbian issues like health funding, reclaiming words from oppressors, diversity, and educating youth. By 2001 when this photo was taken, it occurred annually the weekend before Pride as an unofficial kickoff. Today it exists as She Fest, still the kick off to Pride activities. The Pride Parade for decades has included contingents of people organizing around specific identities, whether it be disabled people, People of Color, immigrants, or sexual orientations. There is power in uniting everyone to build power, but there is also belonging found in events geared towards individual groups, focusing on just their issues that may be overlooked otherwise.

Candy Kayne wearing bisexual flag colors at the festival in 2002. Candy Kayne performed at Pride for many years. The internationally-renowned blues vocalist was openly bisexual and embraced her body at every size. Many queer women were also in her band, including San Diego’s own keyboardist Sue Palmer. Although the LGBTQ+ movement was initially only named the gay movement, then the lesbian and gay rights movement, before acknowledging trans people in the ‘80s and bisexual people in the ‘90s, people who do not describe themselves as gay or lesbian have always been a part of the movement, even before Stonewall Inn.

The parade grew so large in 2003 it was moved up to 11 a.m. on Saturday.

After the parade during the festival, a group of children took turns hitting a rainbow bee piñata. They are inside the Children’s Garden, the family-friendly area of the festival. The area traces its origins to 1991 when a parent support group made up of lesbian and bisexual women and gay men decided they wanted to bring their children to the festival. However, there was nothing fun for the children to do. That parent support group approached Pride about the issue and in 1992 debuted a small Children’s Garden. According to founder Caroline Ramos, the community got behind the idea and fundraised for its expansion in 1993 and beyond. The Children’s Garden makes the festival inclusive for all ages.

Tracie Jade O’Brien, a Black trans woman, leads a transgender community coalition in 2004. That same year she founded the Transgender Day of Empowerment, which is still celebrated today. O’Brien is a living legend, having started a scholarship fund, expanding access to transgender health care and serving as a role model to young trans people. In a video for The Center’s 50th anniversary, she detailed how as a volunteer receptionist, sometimes white LGBTQ+ people would walk out once they saw her at the front desk, a deeply hurtful experience that did not stop her from fighting for everyone in the LGBTQ+ people.

Dykes on Bikes always lead the Pride Parade. The tradition started in San Francisco in 1976 where the iconic name was coined after a group of 25 women on motorcycles led the parade.

Motorcycles are a significant part of lesbian history after World War II shifted the culture around working class women as they took on men’s factory jobs during the war, leading to more independence without a husband and thus ability to form romances with other women. This period was romanticized in Sapphic pulp fiction during the conservative backlash of the next couple decades, linking women who love women with the motorcycle culture of the working class.

Pride is always a time to celebrate victories and spread joy to others. Not all others return that joy. On July 30, 2006 near Balboa Park, a group of men leaving the festival were assaulted by three people wielding a baseball bat and knife while shouting antigay epithets. One victim needed extensive facial reconstruction surgery.

Toni Atkins caught flirting through a face in hole board. Atkins is the successor of Chris Kehoe, following her from City Council to Assembly to State Senate. Atkins had many milestones of her own as she became the first lesbian Speaker of the Assembly then first woman and first LGBTQ+ Senate President Pro Tempore in California. After growing up in poverty in Virginia, Atkins spent her career focused on affordable housing and reproductive rights.

A man holds up a sign reading “Suck it Jesus, Kathy’s My God Now” ahead of comedian Kathy Griffin’s performance.

A few months after the Pride festivities in 2008, California voted by 52% to define marriage as between a man and a woman with the passage of Prop 8. Ahead of the vote, a young generation of LGBTQ+ activists were trained in community organizing. Such advocates as Cara Dessert, Fernando Lopez and Toni Duran all cut their teeth on the No on H8 campaign.

The 300-foot-long rainbow flag has become the traditional conclusion of the San Diego Pride Parade with community members coming together to carry it.

From sequins to feathers, outfits at the Pride Parade symbolize the joy and celebration of the day in defiance of discrimination.

A service member bears a sign reading “Proudly USN (US Navy)/Served… in Silence For 9 Years.” In 2011, San Diego was the first Pride Parade in the nation to have a military contingent of active duty service members. Since they were not permitted to wear their uniforms, the 250 participants wore custom t-shirts for each branch of the military.

With a huge military presence in the community, San Diego celebrated the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell a couple months later. The policy was instituted in 1993 to allow gay people to serve in the military as long as they kept their identity a secret and did not engage in sexual activity. Prior to that, suspected LGBTQ+ people were frequently purged from ranks of the military and dishonorably discharged if caught. While viewed as a step forward to not automatically bar LGBTQ+ people, Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell kept service members in a culture of fear, hostility and silence.

In 2012, the Department of Defense put out blanket permission for active Service Members to wear their uniforms in Pride Parades that year. A San Diego Pride photo of then Navy Senior Chief Dwayne D. Beebe proposing to Jonathan Franqui in the military contingent went viral, representing the intersection of two important political issues of the time: LGBTQ+ people in the military and same-sex marriage.

Here a Palm Springs couple holds up a sign with “We want to get married” crossed out and replaced with “We just got married.” After four years mired in court battles, The Supreme Court decision in Hollingsworth v. Perry re-legalized same-sex marriage in California after Prop 8 was ruled as unconstitutional. It would not be until 2015 in Obergefell v. Hodges when the Supreme Court extended same-sex marriage rights to the entire nation. In honor of this state win, local couples celebrated their recent nuptials in the parade and many drag queens wore wedding dresses.

A Sister of Perpetual Indulgence greeted actress Laverne Cox before the Stonewall Rally in 2014 in which she gave the keynote address. Cox rose to prominence for her role as Sophia Burset in Netflix prison drama “Orange is the New Black,” becoming the first trans person nominated for an Emmy in an acting category.

2015 was a memorable Pride due to a hurricane hitting Mexico, sending torrential rain to interrupt the parade. The year’s grand marshals, the transgender community, went through with a planned die-in to raise awareness of discrimination, violence, murder and suicide the community still faced while others celebrated equal marriage rights.

The Pride Youth Marching Band, pictured here in 2016, is a beloved part of the musical entertainment at the parade, helping LGBTQ+ youth form friendships and learn leadership skills. This volunteer band of junior high and high school students debuted in the rain in 2015 and has performed every year since.

After Dykes on Bikes opens the parade, a contingent of men on motorcycles follows.

Transgender Latina minister Nicole M. Garcia (pictured above) gave the keynote address at interfaith service Light up the Cathedral, an event co-hosted by San Diego Pride and St. Paul’s Cathedral during Pride Week. St. Paul’s was the first cathedral to light up its facade in rainbow for Pride a few years prior. In 2018, devOUT was formed by San Diego Pride as an official way for faith leaders to work together to counter conservative religious messages. The group formed amid a flurry of court cases and laws discriminating against LGBTQ+ people in the name of religious freedom.

Religious organizations have long been part of the LGBTQ+ rights movement, with MCC holding services for LGBTQ+ people and the Catholic support group Dignity in the ‘70s. In fact, The Center was founded partly out of the need for comprehensive LGBTQ+ social services outside of a bar or church.

Yay giant rainbow flag! 2019 had so many contingent the parade moved up to 10 a.m. and it became the first Pride in the world to have a military jet formation fly over the parade route.

The original rainbow flag included turquoise and pink stripes but an eight-strip flag was too hard to print. The simplified rainbow flag remained a steady symbol for many years until the Philadelphia Flag added brown and black stripes to represent People of Color. A few years later, a triangle made up of Trans Flag colors was added on one side, known as the Progress Flag. Most recently, the purple circle on a yellow background from the Intersex Flag was added to the middle of the triangle. The longstanding six-stripe rainbow flag is still a common sight at Pride celebrations.

The COVID-19 pandemic sparked the cancellation of in-person Pride celebrations in 2020 as people isolated to #StopTheSpread. InterPride, the global coalition of Pride organizations, put together a 27-hour virtual program called Global Pride for people to stream live. It was an unprecedented opportunity to hear directly from LGBTQ+ people from around the world, including in countries where it is criminalized.

San Diego Pride did its own livestream in July, with then Executive Director Fernando Lopez streaming from InsideOut for much of the day with performances and interviews with local LGBTQ+ people interspersed. “[It was] one of the most memorable, beautiful things. We all just made the best of that awful situation,” Lopez said.

The pandemic had not ended a year later in 2021 although Black Lives Matter protests had demonstrated people could safely agitate outside in masks without the major spread of disease. Instead of a parade and festival, Pride held a community march with the Black LGBTQ Coalition at the front. Proyecto Trans Latinas, pictured above, won a community service award amid President Trump’s crackdown on the border, endangering LGBTQ+ migrants. Jamie Arangure co-founded the organization in 2018 to advocate for transgender Latina women on both sides of the border.

For many young people who complained about the corporatization of Pride after business sponsors became a huge part of the parade, the march where everyone participated was a way to imagine what Pride of the past could have been like. It had a more subdued tone than other years and was a much smaller event.

Pride returned to a full-scale parade and festival after a two-year pause in 2022. There remained fears about COVID-19 spread and potential violence after a year of right-wing media attacks on trans people and drag queens. Over the past few years, leftist action prompted debate over the checkered history of police, with concerns uniformed law enforcement made Pride unwelcoming to certain groups. Some older activists were staunchly in favor of the inclusion of LGBTQ+ officers who had once faced discrimination themselves. Today’s SDPD and Sheriff’s Department have nondiscrimination policies fought for by activists of the past yet disparities in treatment remain. After a negotiation, law enforcement agencies marched and had festival booths as normal.

Here late Chula Vista Assistant Chief Phil Collum greeted a child during the parade. He was the first openly gay officer in the Chula Vista Police Department and Chula Vista’s first African American lieutenant, captain and assistant chief. After losing his life to cancer in April 2024, friends remembered Collum’s infectious smile and positive attitude.

Pride continued as normal in 2023 with a well-attended event ahead of the Center’s 50th anniversary and InterPride’s 40th anniversary. For the second time, Aromantic and/or Asexual San Diego marched in the parade. Founded by a former Center staff member, the support group connects people who make up the “A” in LGBTQIA+. While asexual might be a familiar term from biology class, many remain ignorant about this label as a sexual orientation and even fewer know about the lack of romantic orientation denoted by “Aromantic.” Aro/Ace SD has connected dozens of people with each other and raised the visibility of this oft-erased group. Here Max Christenfeld waves an asexual flag with Grace beside them as Krista Smith marches behind the truck. A sign on the truck reads “Queer Enough!”

Thank you to these organizations for providing information used in this timeline: San Diego Pride, Lambda Archives, San Diego History Center, San Diego State University, Voice of San Diego, San Diego Magazine, The Word, LeatherFest, The Advocate, and LGBTQhistory.org. The writing and oral histories of these individuals also contributed to this article: Dr. Lillian Faderman, Doug Moore, Nicole Murray Ramirez, Chris Kehoe, Gabriella Garcia, Benny Cartwright, Fernando Lopez, Jen LaBarbera, A.T. Furuya, Carolina Ramos, and Dana Wiegand. A special thanks to Doug Moore, Dana Wiegand and Fernando Lopez for answering specific questions about Pride history.

Discussion about this post